Parser power to manage grammar in text adventures

When I first started playing text adventures, the thing that fascinated me the most was how the game actually understood what I meant. Parsing words and responding to them is easy, but actually determining meaning is something else entirely and it always intrigued me when a game was able to discern meaning from a sentence. Look at this, for example…

Put the key on the table

It seems pretty straightforward. Since the verb “put” is generally understood as placing or dropping something, just drop the key on the table, done. But what happens when the command looks like this?

Put on the jacket

While using the same “put on” verb and preposition combination, the sentence has a completely different meaning. This happens a lot in the English language, as we use certain, subtly different combinations to express different things.

At the same time, we use a lot of constructions in English, where one thing can be expressed in a number of different ways.

Put your hand before your eyes

means the same thing as…

Put your hand in front of your eyes

A good text adventure parser needs to be able to identify these kinds of constructs and make sure to tokenize them accordingly. After all, we do not want to drop our hand down on the floor before putting down our eyes. To us humans, this clearly makes no sense but to a computer program, this takes some schooling.

What I found early on when tackling this issue was that, ideally, this problem is approached in two stages. One, as soon as the individual words are being evaluated, and a second stage that tries to derive meaning from already tokenized individual commands.

Let’s start with the immediate check that is executed every time a new word is tokenized.

def InstaCheck ( self ): """ Check for word combinations that can be instantly replaced, while still parsing the input """ if Tokens.In == globals.thePrep and Tokens.Front == globals.theAdjective: # In front globals.thePrep = Tokens.Before globals.thePrepString = self.TokenLookup ( Tokens.Before ) globals.theAdjective = None globals.theAdjectiveString = None

Every time a command is tokenized, InstaCheck() is called. This means the call is inside the parser loop that iterates through every word in the player’s command.

The snippet above checks to see if the player has entered the preposition in and the adjective front and immediately replaces the preposition meaning with before. This, of course, changes the entire meaning of the sentence right there from “in” to “before.” Naturally, the routine also has to do some cleanup and clear the adjective because it is no longer needed—in fact, it HAS TO be removed because its meaning as an individual word has disappeared.

Coming out of InstaCheck() we now have changed an input like Put your hands in front of your eyes to Put your hands before your eyes. Naturally, the same technique will be put to work for many other expressions we use in English.

But that’s not all yet. We also need a second logic stage to determine meaning, which is executed after the entire player command has been parsed and tokenized. This is necessary because in many instances, the order of the words is every bit as important as their immediate meaning.

If we take the example from above again, Put the key on the table has an entirely different meaning than Put on the jacket for a few simple reasons. Aside from a subject, one of the sentences has a direct object associated with the predicate.

Therefore, checking if the sentence has an object allows us to determine, which version of “put on” the player was referring to. Unlike the InstaCheck()that is based mostly on the existence on words themselves, this stage requires a more grammatical analysis and, as you will see, its scope is much, much wider.

But let’s start simple and just focus on our “put on” problem for now.

def Grammar ( self ): """ Inspect input tokens to derive additional meaning from prepositions, adjectives, etc. """ if Tokens.Drop == globals.theVerb: if Tokens.On == globals.thePrep: # PUT ON globals.thePrep = None if not globals.theNoun2: # without second noun globals.theVerb = Tokens.Wear # i.e. Put on the jacket else: globals.theVerb = Tokens.PutOn # i.e. Put the key on the table

It is just a simple comparison, as you can see, but in terms of the meaning, it makes a huge difference. Suddenly, “put” “on” will become either “Put on” or “wear,” depending on the sentence structure.

As you will find, using this sort of grammar post-tokenizing stage is very helpful to create specific meaning for a wide variety of verbs which allows for easier and cleaner checks in the game itself. Instead of determining if the user entered Tokens.Put and Tokens.On whenever necessary during gameplay and then responding to it, we have just simplified the check to Tokens.PutOn. This way, each Token actually carries a lot more meaning and prevents errors down the line where input might accidentally be misinterpreted.

Other verbs that can be easily specified this way are “put in,” “fill in,” “fill with” and many more, allowing the player to use a variety of commands to have the same meaning, or to derive special meaning from the grammar of their input.

Another area where this kind of lexical distinction comes in handy is in the use of adjectives. Imagine, if you will, that you have a number of keys in the game. It’s a common occurrence because the odds are you will have a number of locked doors and each may require its own key. So, you have a small key, a skeleton key, a brass key and, perhaps, a golden key. How do you distinguish between them?

As you can see, the unique identifier for each key is the adjective that describes it. This allows us to create a unique token for each respective key early on, right after the parser has finished tokenizing the words. Why not in the InstaCheck()? Because there is a good chance that so early in the parsing we do not yet know which noun the adjective refers to or if it an adjective at all.

def Grammar ( self ): """ Inspect input tokens to derive additional meaning from prepositions, adjectives, etc. """ if Tokens.Small == globals.theAdjective and Tokens.Key == globals.theNoun: # Small Key globals.theNoun = Tokens.SmallKey globals.theNounString = self.TokenLookup ( Tokens.SmallKey ) if Tokens.Brass == globals.theAdjective and Tokens.Key == globals.theNoun: # Brass key globals.theNoun = Tokens.BrassKey globals.theNounString = self.TokenLookup ( Tokens.BrassKey ) if Tokens.Skeleton == globals.theAdjective and Tokens.Key == globals.theNoun: # Skeleton key globals.theNoun = Tokens.SkeletonKey globals.theNounString = self.TokenLookup ( Tokens.SkeletonKey ) if Tokens.Gold == globals.theAdjective and Tokens.Key == globals.theNoun: # Gold key globals.theNoun = Tokens.GoldKey globals.theNounString = self.TokenLookup ( Tokens.GoldKey ) if Tokens.Lamp == globals.theNoun and Tokens.Oil == globals.theNoun2: # Lamp oil globals.theNoun = Tokens.Oil globals.theNounString = self.TokenLookup ( Tokens.Oil ) globals.theNoun2 = None globals.theNoun2String = None

Adjectives are a bit of a tricky bunch because they often pose as nouns. When you take the Skeleton Key, for example, the word skeleton is actually a noun, though used as an adjective in this context. There are a number of ways to handle this. The easiest is to make sure there are no skeletons in your game and then simply define skeleton as an adjective in your vocabulary or to make a determination in the code, which brings us right back to the InstaCheck() routine. See how it all fits together?

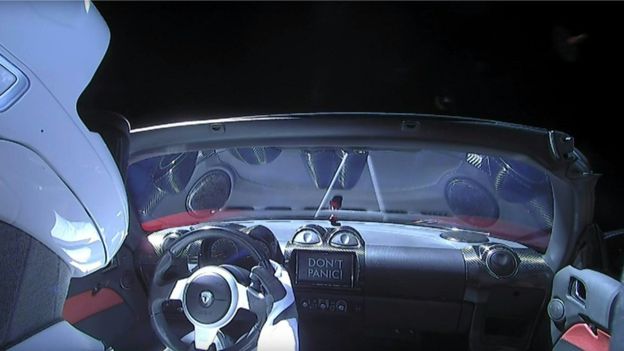

Before I go, I want to give a quick shout-out to the SpaceX Heavy Falcon launch of yesterday. Not only because it was quite an experience to watch and an incredible engineering achievement, but because of the beautiful “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” homage with the “Don’t Panic” sign in the car that is now floating in space for all time to come. It proved that Elon Musk is a true super nerd, and I like it! He makes us all proud.

Hi Lucas

Did you ever get to the end of writing the game?

Am just learning python and am attempting to recreate the infocom parser in it as a way of learning the language, so any pointers/code you could provide would be most appreciated.

Still actually trying to decide how to hold all the known words/synoyns/grammer rules, i think a new class but am working on it still – cheers Neil

Hi Neil,

No, I have not been able to complete the game. A lot of other things came up and with that workload, the project fell by the wayside. I toyed at one point with the idea of re-writing the parser using a proper rule-based system instead of the one I explaining in my posts. That would make it more declarative overall and work closer to the way traditional text adventures actually parsed the input, but I’ve never had the chance to really work on it.

To do that I’d create a “VerbRule” class for example that adds itself to a global dictionary. That way you can declare meanings for specific rooms and then remove that rule whenever it is no longer needed because it would allow you to add verbs at any point in the game and you don’t have to rely on that large static data initialization I have in place in my current system.

Good luck with your own project.